Right-wing populists are exploiting the migration issue in both the United States and Europe, but dismissing their arguments would be a mistake. Instead, an honest assessment of the economic and regime-change policies that fuel migration is needed, reports Andrew Spannaus.

By Andrew Spannaus

Anti-establishment political forces in the both the United States and Europe have seized on the issue of illegal immigration, seen by many voters as a threat to both economic well-being and cultural identity, as a key components of their electoral strategies. While Donald Trump has made the wall with Mexico one of his priorities and has worked to uphold a ban on immigration from a number of Muslim nations, in Europe, numerous political parties have been following this script for many years.

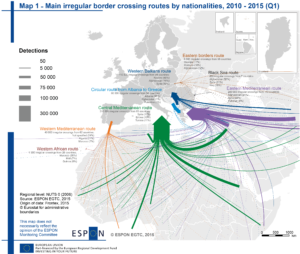

Main irregular border crossing routes into Europe. Source: European Union

Drawing on the economic anxiety of the middle class, tied to fear of being undercut by low-wage work, and worries concerning terrorism and cultural changes, anti-immigrant sentiment has become a key weapon of right-wing populist forces. These forces have drawn on the narrative of governing elites that pursue their own, limited interests, while seeking to hold down the majority of society through policies that rob them of both economic opportunity and their cultural heritage.

The sentiment is significant and growing, contributing to the growth in support for populist causes in a series of recent elections in Europe – including in Germany and Austria – as well as a noticeable shift in attitudes towards immigration in the past two years, even among more moderate segments of the population.

A major factor has been the recent surge in migrants coming from the Middle East and Africa – mainly the consequence of the disastrous “regime change” wars starting with the invasion of Iraq in 2003, through to the more recent conflicts in Libya and Syria – and the resulting perception of an impossible-to-stop “invasion” that is changing the character of Europe.

International organizations that deal directly with the management of undocumented migrant flows are working actively to combat this perception. They stress not only the importance of defending the human rights of migrants under international law, but also that even with the recent peak – that exceeded one million in 2015, but dropped back to below 200,000 last year – the numbers involved are manageable.

Further, migration should not be seen as a threat, but rather as an opportunity, international organizations stress.

Counter-Narrative

This approach was discussed in depth in Vienna, Austria last month, during events for the “2017 International Migrants Day” sponsored by the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE) and the International Organization for Migration (IOM), which works closely with the United Nations on migration.

In opening a high-level panel discussion on Dec. 19 entitled “Perception is not reality; Towards a new narrative of migration”, OSCE Secretary General Thomas Greminger spoke of the need to develop a counter-narrative to that currently dominating public discussion. This involves highlighting the positive contributions of migrants in economic terms, based, for example, on the circulation of skills and knowledge among different countries.

Immediately afterwards, Gervais Apparve, Special Policy Advisor to the IOM, waded into the thorny issue of the relationship between migration and globalization. Apparve began by citing Thomas Friedman’s 2005 book “The World is Flat,” which speaks of the disappearance of barriers to trade, the exchange of resources, and the transfer of capital, creating an interconnected world. Apparve lamented that this interconnectedness has not yet been extended to the area of unrestricted mobility, which for the most part remains the province only of the well-to-do.

With this comment, the IOM representative inadvertently exposed the weakness in the approach taken by international organizations: the perceived link between migration and the economic policies of globalization in recent decades.

Globalization, Migration and Paranoia

There is a widespread, and understandable, reaction against the disappearance of barriers in areas such as trade and the transfer of capital, which have had negative effects for many in the Western world. The reduction of regulations on commerce and finance has often allowed large corporations to exploit low-cost labor and prioritize short-term financial gain over stable investment. The result has been a race to the bottom in numerous sectors, entailing job losses, instability and poverty for the (former) middle class.

Yet, the attempt to create a positive attitude towards migrants from impoverished areas by linking their plight to globalization can inadvertently stoke fears that migration is part of a deliberate process to lower the living standards of wide segments of the population, creating competition for scarce resources among those who are unable to access the massive wealth being concentrated near the top of society.

The organizations that seek to combat negative views of migration seem reluctant to recognize that aiming to build a positive narrative by emphasizing benefits rather than risks is not enough. Indeed, changing negative views without dealing with the underlying political and economic problems that fuel the current turmoil could prove impossible.

In political terms, the relationship is obvious. Opposition to political elites, as well as “political correctness,” is often linked to distrust of the elites’ economic policies. Indeed almost all of the populist groups that promote anti-immigration views also draw on economic discontent. In Europe, they attack European Union economic policies, just as outsiders attack Wall Street in the United States.

Although their solutions may be circumspect, it would be a mistake to call anti-establishment forces insincere, or to dismiss them as lacking serious policy proposals. Instead, the issues they raise should be tackled directly.

If governments ignore the issues, they contribute to the image of a political class refusing to admit mistakes, an image all too easily exploited by right-wing populists. The elite’s head-in-the-sand approach confirms the criticism from outsiders that status quo politicians are avoiding accountability and blocking change, which opens the door to whomever effectively identifies the problems felt by the population, regardless of whether they propose valid alternatives or not.

Reality-Based Discussion

On the issue of migration, moving towards what the international community calls a “reality-based discussion,” i.e. avoiding exaggerated fears that fuel racist attitudes and closure, will be difficult without facing head on the negative effects of economic globalization in recent decades, as well as the results of foreign interventions and regime change wars in the Middle East and North Africa.

As Swiss parliamentarian and chair of the OSCE Parliamentary Assembly’s Ad Hoc Committee on Migration Filippo Lombardi recently stated, policymakers must “honestly assess the political mistakes of recent years,” which have destabilized so many countries and created the conditions for mass migration from Africa and the Middle East.

“Only such an honest and responsible approach can lead to solving the crisis we are now facing,” he said.

Seeking to shift the overall view of migration from negative to positive, the new narrative of the international community is based on several assertions: first of all, that migration is perfectly normal, it has always existed, and neither can nor should be stopped. Indeed, the overall number of migrants to Europe, including those who move for work, study or family reasons, remains at a level of over two million per year; thus a few hundred thousand undocumented arrivals should be entirely manageable in this context.

The goal expressed by many participants in the Vienna event, for example, is to eliminate the distinction made between those who come through official channels, and the migrants who arrive undocumented, making the dangerous journey through Northern Africa and the Mediterranean Sea. This is not an easy sell with public opinion at this time though, as in the latter case the cost of the migrants’ survival is covered by the public welfare system, in the hope they will eventually be integrated into society and the work force.

This brings us to another argument: that migrants actually provide a positive contribution to the economy, with many European countries’ low birth rates lagging below replacement levels and the population aging rapidly. An influx of younger workers from other nations contributes to rebalancing the workforce in demographic terms, thus avoiding a situation in which the ratio of active workers to retirees becomes so low as to call into question the sustainability of pension and welfare systems.

Beyond Narratives

While the aging of European populations is a problem, here again there are some hidden assumptions that indicate the need for a deeper policy shift, beyond simply “changing the narrative.” Demographic surveys confirm that people marry and put off having children in part due to economic circumstances. Improving the financial prospects of young workers, or getting them out of the ranks of the unemployed, could have a rapid impact on birth rates and population trends in general.

It is also somewhat cynical to claim that poor immigrants provide a positive economic contribution based on the fact that they are willing to work low-wage jobs. It’s one thing to encourage the fruitful exchange of skills and knowledge among different populations, or celebrate diversity as a way of enriching culture; it is quite another to undermine wages by ensuring a vast pool of desperate workers available at any time.

This contradiction brings the discussion back to the economic policies associated with globalization, putting both low-wage European workers and migrants in the same boat, so to speak. Playing destitute migrants against unemployed Europeans is not a recipe for social cohesiveness; rather, it shows the deeper policy problems facing the Western world as a whole.

A return to an approach based on promoting a decent standard of living even among those doing labor-intensive jobs, could go a long way towards reducing the fears in European nations regarding the arrival of undocumented migrants. Extending such an approach globally, by making a serious commitment to combatting poverty in the least developed countries around the world, would also change the equation for many migrants, making migration a choice rather than a necessity in order to survive.

Andrew Spannaus is a journalist and strategic analyst based in Milan, Italy. He is the founder of Transatlantico.info, that provides news and analysis to Italian institutions and businesses. He has published the books “Perché vince Trump” (Why Trump is Winning – June 2016) and “La rivolta degli elettori” (The Revolt of the Voters – July 2017).

The views expressed in this article are the sole responsibility of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of the Blog!

No comments:

Post a Comment