By Whitney Webb

Since the U.S. killed Iranian General Qassem Soleimani and Iraqi militia leader Abu Mahdi al-Muhandis earlier this month, the official narrative has held that their deaths were necessary to prevent a vague, yet allegedly imminent, threat of violence towards Americans, though President Trump

has since claimed whether or not Soleimani or his Iraqi allies posed an imminent threat “doesn’t really matter.”

While the situation between Iran, Iraq and the U.S. appears to have de-escalated substantially, at least for now, it is worth revisiting the lead-up to the recent U.S.-Iraq/Iran tensions up to the Trump-mandated killing of Soleimani and Abu Mahdi al-Muhandis in order to understand one of the most overlooked yet relevant drivers behind Trump’s current policy with respect to Iraq: preventing China from expanding its foothold in the Middle East. Indeed, it has been alleged that even the timing of Soleimani’s assassination was directly related to his diplomatic role in Iraq and his push to help Iraq secure its oil independence, beginning with the implementation of a new massive oil deal with China.

While

recent rhetoric in the media

has dwelled on the extent of Iran’s influence in Iraq, China’s recent dealings with Iraq — particularly in its oil sector — are to blame for much of what has transpired in Iraq in recent months, at least according to Iraq’s Prime Minister Adel Abdul-Mahdi, who is currently serving in a caretaker role.

Much of the U.S. pressure exerted on Iraq’s government with respect to China has reportedly taken place covertly and behind closed doors, keeping the Trump administration’s concerns over China’s growing ties to Iraq largely out of public view, perhaps over concerns that a public scuffle could exacerbate the U.S.-China “trade war” and endanger efforts to resolve it. Yet, whatever the reasons may be, evidence strongly suggests that the U.S. is equally concerned about China’s presence in Iraq as it is with Iran’s. This is because China has the means and the ability to dramatically undermine not only the U.S.’ control over Iraq’s oil sector but the entire petrodollar system on which the U.S.’ status as both a financial and military superpower directly depends.

Behind the curtain, a different narrative for Iraq-US Tensions

Iraq’s caretaker Prime Minister Adel Abdul-Mahdi gave a series of remarks on January 5, during a parliamentary session that received surprisingly little media attention. During the session, which also saw Iraq’s Parliament approve the removal of all foreign (including American) troops from the country, Abdul-Mahdi made a series of claims about the lead-up to the recent situation that placed Iraq at the heart of spiking U.S.-Iran tensions.

During that session, only part of Abdul-Mahdi’s statements were broadcast on television, after the Iraqi Speaker of the House — Mohammed Al-Halbousi, who has

a close relationship with Washington — requested the video feed be cut. Al-Halbousi oddly attended the parliamentary session even though it was boycotted by his allied Sunni and Kurdish representatives.

After the feed was cut, MPs who were present wrote down Abdul-Mahdi’s remarks, which were then given to the Arabic news outlet

Ida’at.

Per that transcript, Abdul-Mahdi stated that:

The Americans are the ones who destroyed the country and wreaked havoc on it. They have refused to finish building the electrical system and infrastructure projects. They have bargained for the reconstruction of Iraq in exchange for Iraq giving up 50% of oil imports. So, I refused and decided to go to China and concluded an important and strategic agreement with it. Today, Trump is trying to cancel this important agreement.”

Abdul-Mahdi continued his remarks, noting that pressure from the Trump administration over his negotiations and subsequent dealings with China grew substantially over time, even resulting in death threats to himself and his defense minister:

After my return from China, Trump called me and asked me to cancel the agreement, so I also refused, and he threatened [that there would be] massive demonstrations to topple me. Indeed, the demonstrations started and then Trump called, threatening to escalate in the event of non-cooperation and responding to his wishes, whereby a third party [presumed to be mercenaries or U.S. soldiers] would target both the demonstrators and security forces and kill them from atop the highest buildings and the US embassy in an attempt to pressure me and submit to his wishes and cancel the China agreement.”

“I did not respond and submitted my resignation and the Americans still insist to this day on canceling the China agreement. When the defense minister said that those killing the demonstrators was a third party, Trump called me immediately and physically threatened myself and the defense minister in the event that there was more talk about this third party.”

Very few English language outlets

reported on Abdul-Mahdi’s comments. Tom Luongo,

a Florida-based Independent Analyst and publisher of The Gold Goats ‘n Guns Newsletter, told

MintPress that the likely reasons for the “surprising” media silence over Abdul-Mahdi’s claims were because “It never really made it out into official channels…” due to the cutting of the video feed during Iraq’s Parliamentary session and due to the fact that “it’s very inconvenient and the media — since Trump is doing what they want him to do, be belligerent with Iran, protected Israel’s interests there.”

“They aren’t going to contradict him on that if he’s playing ball,” Luongo added, before continuing that the media would nonetheless “hold onto it for future reference….If this comes out for real, they’ll use it against him later if he tries to leave Iraq.” “Everything in Washington is used as leverage,” he added.

Given the lack of media coverage and the cutting of the video feed of Abdul-Mahdi’s full remarks, it is worth pointing out that the narrative he laid out in his censored speech not only fits with the timeline of recent events he discusses but also the tactics known to have been employed behind closed doors by the Trump administration, particularly after Mike Pompeo left the CIA to become Secretary of State.

For instance, Abdul-Mahdi’s delegation to China ended on September 24, with the protests against his government that Trump reportedly threatened to start on October 1. Reports of a “third side” firing on Iraqi protesters were picked up by major media outlets at the time, such as in

this BBC report which stated:

Reports say the security forces opened fire, but another account says unknown gunmen were responsible….a source in Karbala told the BBC that one of the dead was a guard at a nearby Shia shrine who happened to be passing by. The source also said the origin of the gunfire was unknown and it had targeted both the protesters and security forces. (emphasis added)”

U.S.-backed protests in other countries, such as in Ukraine in 2014, also saw evidence of a “

third side” shooting both protesters and security forces alike.

After six weeks of

intense protests, Abdul-Mahdi

submitted his resignation on November 29, just

a few days after Iraq’s Foreign Minister praised the new deals, including the “oil for reconstruction” deal, that had been signed with China. Abdul-Mahdi has since stayed on as Prime Minister in a caretaker role until Parliament decides on his replacement.

Abdul-Mahdi’s claims of the covert pressure by the Trump administration are buttressed by the use of similar tactics against Ecuador, where, in July 2018, a U.S. delegation at the United Nations

threatened the nation with punitive trade measures and the withdrawal of military aid if Ecuador moved forward with the introduction of a UN resolution to “protect, promote and support breastfeeding.”

The New York Times reported at the time that the U.S. delegation was seeking to promote the interests of infant formula manufacturers. If the U.S. delegation is willing to use such pressure on nations for promoting breastfeeding over infant formula, it goes without saying that such behind-closed-doors pressure would be significantly more intense if a much more lucrative resource, e.g. oil, were involved.

Regarding Abdul-Mahdi’s claims, Luongo told MintPress that it is also worth considering that it could have been anyone in the Trump administration making threats to Abdul-Mahdi, not necessarily Trump himself. “What I won’t say directly is that I don’t know it was Trump at the other end of the phone calls. Mahdi, it is to his best advantage politically to blame everything on Trump. It could have been Mike Pompeo or Gina Haspel talking to Abdul-Mahdi… It could have been anyone, it most likely would be someone with plausible deniability….This [Mahdi’s claims] sounds credible… I firmly believe Trump is capable of making these threats but I don’t think Trump would make those threats directly like that, but it would absolutely be consistent with U.S. policy.”

Luongo also argued that the current tensions between U.S. and Iraqi leadership preceded the oil deal between Iraq and China by several weeks, “All of this starts with Prime Minister Mahdi starting the process of opening up the Iraq-Syria border crossing and that was announced in August. Then, the Israeli air attacks happened in September to try and stop that from happening, attacks on PMU forces on the border crossing along with the ammo dump attacks near Baghdad… This drew the Iraqis’ ire… Mahdi then tried to close the air space over Iraq, but how much of that he can enforce is a big question.”

As to why it would be to Mahdi’s advantage to blame Trump, Luongo stated that Mahdi “can make edicts all day long, but, in reality, how much can he actually restrain the U.S. or the Israelis from doing anything? Except for shame, diplomatic shame… To me, it [Mahdi’s claims] seems perfectly credible because, during all of this, Trump is probably or someone else is shaking him [Mahdi] down for the reconstruction of the oil fields [in Iraq]…Trump has explicitly stated “we want the oil.”’

As Luongo noted, Trump’s interest in the U.S. obtaining a significant share of Iraqi oil revenue is hardly a secret. Just last March, Trump

asked Abdul-Mahdi “How about the oil?” at the end of a meeting at the White House, prompting Abdul-Mahdi to ask “What do you mean?” To which Trump responded “Well, we did a lot, we did a lot over there, we spent trillions over there, and a lot of people have been talking about the oil,” which was widely interpreted as Trump asking for part of Iraq’s oil revenue in exchange for the steep costs of the U.S.’ continuing its now unwelcome military presence in Iraq.

With Abdul-Mahdi having rejected Trump’s “oil for reconstruction” proposal in favor of China’s, it seems likely that the Trump administration would default to so-called “gangster diplomacy” tactics to pressure Iraq’s government into accepting Trump’s deal, especially given the fact that China’s deal was a much better offer. While Trump demanded half of Iraq’s oil revenue in exchange for completing reconstruction projects (according to Abdul-Mahdi), the deal that was signed between Iraq and China would see

around 20 percent of Iraq’s oil revenue go to China in exchange for reconstruction. Aside from the potential loss in Iraq’s oil revenue, there are many reasons for the Trump administration to feel threatened by China’s recent dealings in Iraq.

The Iraq-China oil deal – a prelude to something more?

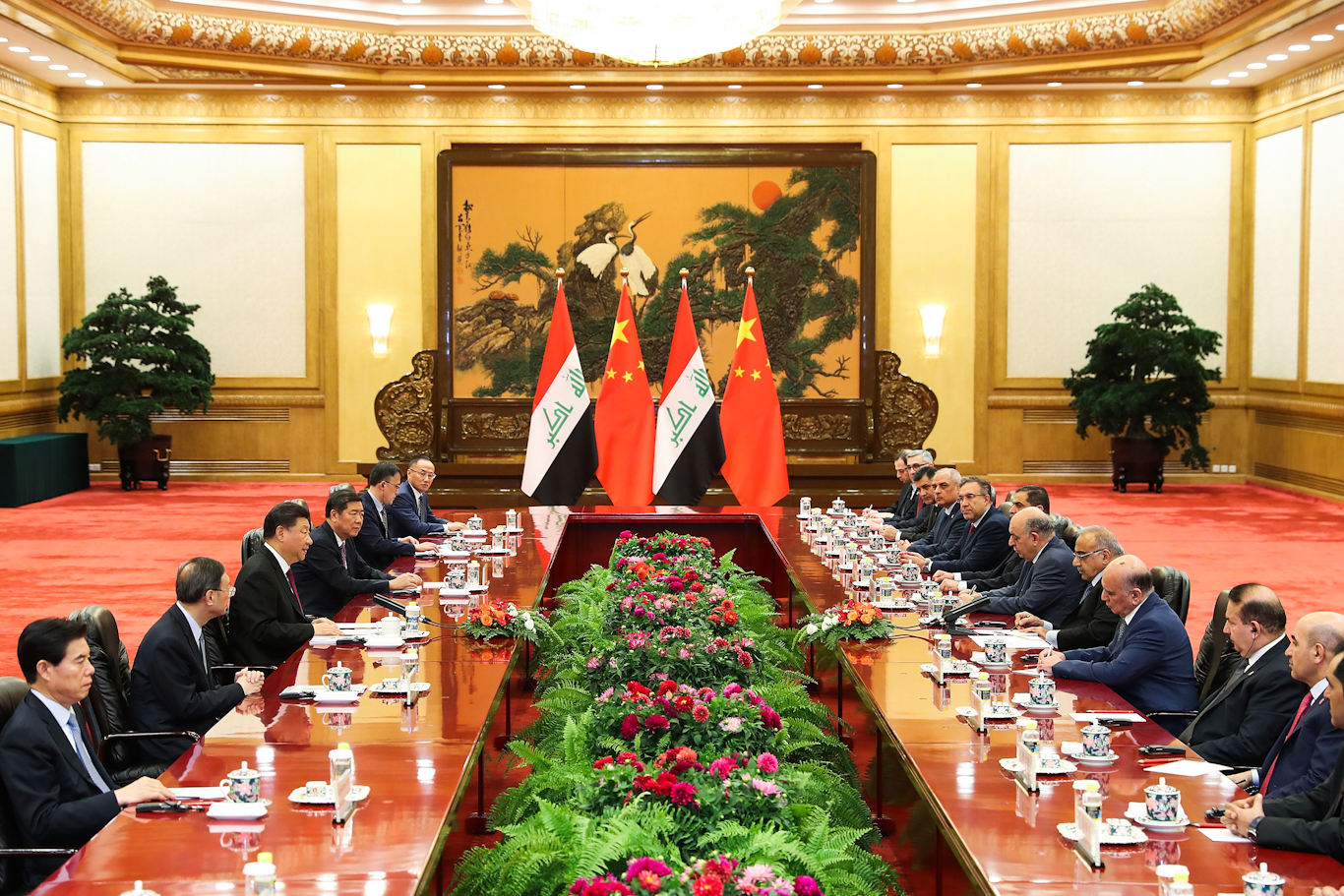

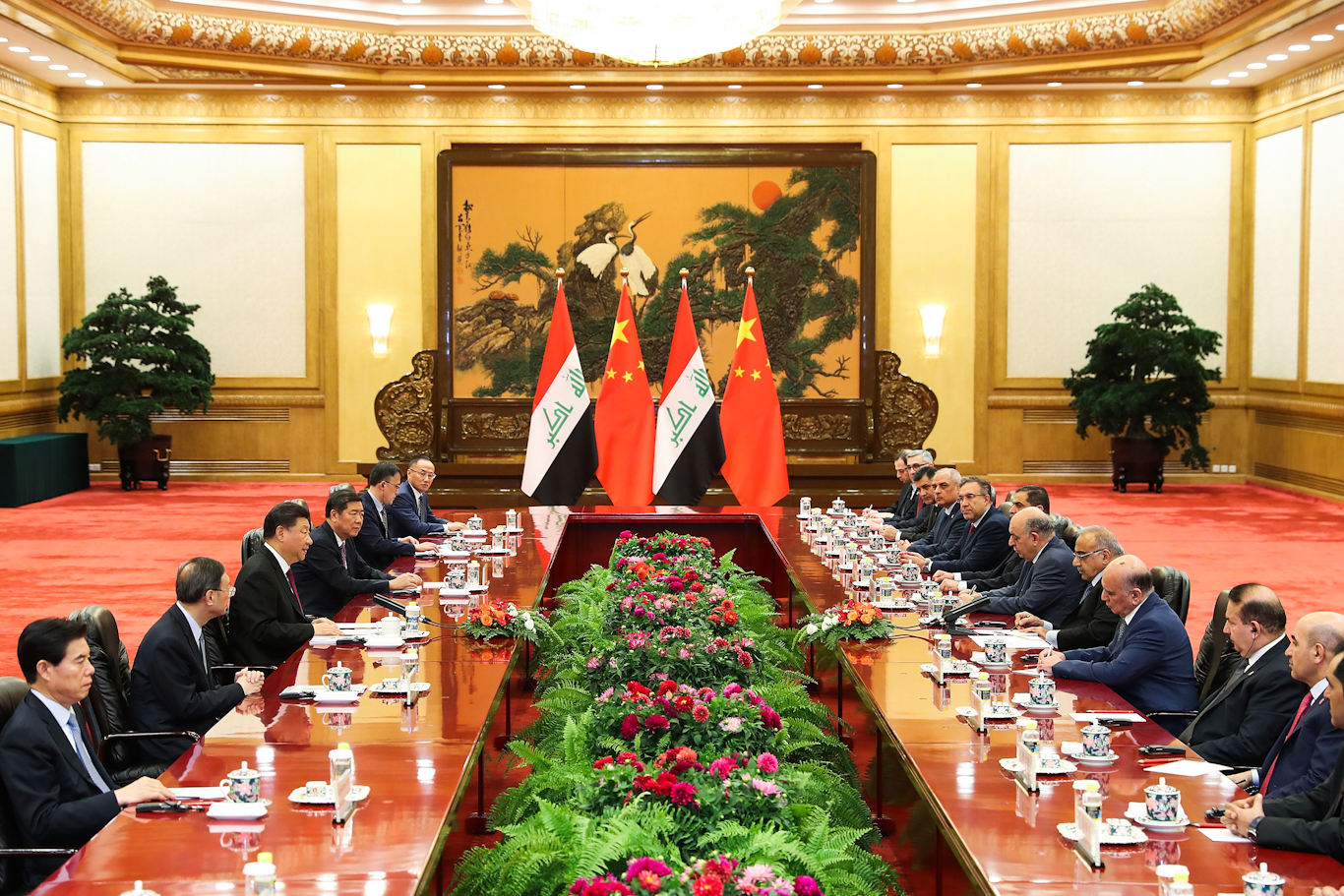

When Abdul-Mahdi’s delegation traveled to Beijing last September, the “oil for reconstruction” deal was only

one of eight total agreements that were established. These agreements cover a range of areas, including financial, commercial, security, reconstruction, communication, culture, education and foreign affairs in addition to oil. Yet, the oil deal is by far the most significant.

Per the agreement, Chinese firms will work on various reconstruction projects in exchange for roughly 20 percent of Iraq’s oil exports, approximately 100,00 barrels per day, for a period of 20 years. According to

Al-Monitor, Abdul-Mahdi had the following to say about the deal: “We agreed [with Beijing] to set up a joint investment fund, which the oil money will finance,” adding that the agreement prohibits China from monopolizing projects inside Iraq, forcing Bejing to work in cooperation with international firms.

The agreement is similar to one

negotiated between Iraq and China in 2015 when Abdul-Mahdi was serving as Iraq’s oil minister. That year, Iraq joined China’s Belt and Road Initiative in a deal that also involved exchanging oil for investment, development and construction projects and saw China awarded several projects as a result. In a notable similarity to recent events, that deal was put on hold due to “political and security tensions” caused by unrest and the surge of ISIS in Iraq, that is until Abdul-Mahdi saw Iraq

rejoin the initiative again late last year through the agreements his government signed with China last September.

Notably, after recent tensions between the U.S. and Iraq over the assassination of Soleimani and the U.S.’ subsequent refusal to remove its troops from Iraq despite parliament’s demands, Iraq quietly announced that it would dramatically increase its oil exports to China to

triple the amount established in the deal signed in September. Given Abdul-Mahdi’s recent claims about the true forces behind Iraq’s recent protests and Trump’s threats against him being directly related to his dealings with China, the move appears to be a not-so-veiled signal from Abdul-Mahdi to Washington that he plans to deepen Iraq’s partnership with China, at least for as long as he remains in his caretaker role.

Iraq’s decision to dramatically increase its oil exports to China came just one day after the U.S. government

threatened to cut off Iraq’s access to its central bank account, currently held at the Federal Reserve Bank of New York, an account that

currently holds $35 billion in Iraqi oil revenue. The account was

set up after the U.S. invaded and began occupying Iraq in 2003 and Iraq currently removes between $1-2 billion per month to cover essential government expenses. Losing access to its oil revenue stored in that account would lead to the “

collapse” of Iraq’s government, according to Iraqi government officials who spoke to

AFP.

Though Trump publicly promised to rebuke Iraq for the expulsion of U.S. troops via sanctions, the threat to cut off Iraq’s access to its account at the NY Federal Reserve Bank was delivered privately and directly to the Prime Minister, adding further credibility to Abdul-Mahdi’s claims that Trump’s most aggressive attempts at pressuring Iraq’s government are made in private and directed towards the country’s Prime Minister.

Though Trump’s push this time was about preventing the expulsion of U.S. troops from Iraq, his reasons for doing so may also be related to concerns about China’s growing foothold in the region. Indeed, while Trump has now lost his desired share of Iraqi oil revenue (50 percent) to China’s counteroffer of 20 percent, the removal of U.S. troops from Iraq may see American troops replaced with their Chinese counterparts as well, according to Tom Luongo.

“All of this is about the U.S. maintaining the fiction that it needs to stay in Iraq…So, China moving in there is the moment where they get their toe hold for the Belt and Road [Initiative],” Luongo argued. “That helps to strengthen the economic relationship between Iraq, Iran and China and obviating the need for the Americans to stay there. At some point, China will have assets on the ground that they are going to want to defend militarily in the event of any major crisis. This brings us to the next thing we know, that Mahdi and the Chinese ambassador discussed that very thing in the wake of the Soleimani killing.”

Indeed, according to news reports, Zhang Yao — China’s ambassador to Iraq — “

conveyed Beijing’s readiness to provide military assistance” should Iraq’s government request it soon after Soleimani’s assassination. Yao made the offer a day after Iraq’s parliament voted to expel American troops from the country. Though it is currently unknown how Abdul-Mahdi responded to the offer, the timing likely caused no shortage of concern among the Trump administration about its rapidly waning influence in Iraq. “You can see what’s coming here,” Luongo told

MintPress of the recent Chinese offer to Iraq, “China, Russia and Iran are trying to cleave Iraq away from the United States and the U.S. is feeling very threatened by this.”

Russia is also playing a role in the current scenario as Iraq initiated talks with Moscow regarding the

possible purchase of one of its air defense systems last September, the same month that Iraq signed eight deals, including the oil deal with China. Then, in the wake of Soleimani’s death, Russia

again offered the air defense systems to Iraq to allow them to better defend their air space. In the past, the U.S.

has threatened allied countries with sanctions and other measures if they purchase Russian air defense systems as opposed to those manufactured by U.S. companies.

The U.S.’ efforts to curb China’s growing influence and presence in Iraq amid these new strategic partnerships and agreements are limited, however, as the U.S. is

increasingly relying on China as part of its Iran policy, specifically in its goal of reducing Iranian oil export to zero. China remains Iran’s main crude oil and condensate importer, even after it reduced its imports of Iranian oil significantly following U.S. pressure last year. Yet, the U.S. is

now attempting to pressure China to stop buying Iranian oil completely or face sanctions while also attempting to privately sabotage the China-Iraq oil deal. It is highly unlikely China will concede to the U.S. on both, if any, of those fronts, meaning the U.S. may be forced to choose which policy front (Iran “containment” vs. Iraq’s oil dealings with China) it values more in the coming weeks and months.

Furthermore, the recent signing of the “phase one” trade deal with China revealed another potential facet of the U.S.’ increasingly complicated relationship with Iraq’s oil sector given that the trade deal

involves selling U.S. oil and gas to China at very low cost, suggesting that the Trump administration may also see the Iraq-China oil deal result in Iraq emerging as a potential competitor for the U.S. in selling cheap oil to China, the world’s top oil importer.

The Petrodollar and the Phantom of the Petroyuan

In his televised statements last week following Iran’s military response to the U.S. assassination of General Soleimani, Trump insisted that the U.S.’ Middle East policy is no longer being directed by America’s vast oil requirements. He

stated specifically that:

Over the last three years, under my leadership, our economy is stronger than ever before and America has achieved energy independence. These historic accomplishments changed our strategic priorities. These are accomplishments that nobody thought were possible. And options in the Middle East became available. We are now the number-one producer of oil and natural gas anywhere in the world. We are independent, and we do not need Middle East oil. (emphasis added)”

Yet, given the centrality of the recent Iraq-China oil deal in guiding some of the Trump administration’s recent Middle East policy moves, this appears not to be the case. The distinction may lie in the fact that, while the U.S. may now be less dependent on oil imports from the Middle East, it still very much needs to continue to dominate how oil is traded and sold on international markets in order to maintain its status as both a global military and financial superpower.

Indeed, even if the U.S. is importing less Middle Eastern oil, the petrodollar system — first forged in the 1970s — requires that the U.S. maintains enough control over the global oil trade so that the world’s largest oil exporters, Iraq among them, continue to sell their oil in dollars. Were Iraq to sell oil in another currency, or trade oil for services, as it plans to do with China per the recently inked deal, a significant portion of Iraqi oil would cease to generate a demand for dollars, violating the key tenet of the petrodollar system.

The takeaway from the petrodollar phenomenon is that as long as countries need oil, they will need the dollar. As long as countries demand dollars, the U.S. can continue to go into massive amounts of debt to fund its network of global military bases, Wall Street bailouts, nuclear missiles, and tax cuts for the rich.”

Thus, the use of the petrodollar has created a system whereby U.S. control of oil sales of the largest oil exporters is necessary, not just to buttress the dollar, but also to support its global military presence. Therefore, it is unsurprising that the issue of the U.S. troop presence in Iraq and the issue of Iraq’s push for oil independence against U.S. wishes have become intertwined. Notably, one of the architects of the petrodollar system and the man who infamously described U.S. soldiers as “dumb, stupid animals to be used as pawns in foreign policy”, former Secretary of State Henry Kissinger, has been

advising Trump and informing his China policy since 2016.

This take was also expressed by economist Michael Hudson,

who recently noted that U.S. access to oil, dollarization and U.S. military strategy are intricately interwoven and that Trump’s recent Iraq policy is intended “to escalate America’s presence in Iraq to keep control of the region’s oil reserves,” and, as Hudson says, “to back Saudi Arabia’s Wahabi troops (ISIS, Al Qaeda in Iraq, Al Nusra and other divisions of what are actually America’s foreign legion) to support U.S. control of Near Eastern oil as a buttress of the U.S. dollar.”

Hudson further asserts that it was Qassem Soleimani’s efforts to promote Iraq’s oil independence at the expense of U.S. imperial ambitions that served one of the key motives behind his assassination.

America opposed General Suleimani above all because he was fighting against ISIS and other U.S.-backed terrorists in their attempt to break up Syria and replace Assad’s regime with a set of U.S.-compliant local leaders – the old British “divide and conquer” ploy. On occasion, Suleimani had cooperated with U.S. troops in fighting ISIS groups that got “out of line” meaning the U.S. party line. But every indication is that he was in Iraq to work with that government seeking to regain control of the oil fields that President Trump has bragged so loudly about grabbing. (emphasis added)”

Hudson adds that “…U.S. neocons feared Suleimani’s plan to help Iraq assert control of its oil and withstand the terrorist attacks supported by U.S. and Saudi’s on Iraq. That is what made his assassination an immediate drive.”

While other factors — such as

pressure from U.S. allies such as Israel — also played a factor in the decision to kill Soleimani, the decision to assassinate him on Iraqi soil just hours before he was set to meet with Abdul-Mahdi in a diplomatic role suggests that the underlying tensions caused by Iraq’s push for oil independence and its oil deal with China did play a factor in the timing of his assassination. It also served as a threat to Abdul-Mahdi, who has claimed that the U.S. threatened to kill both him and his defense minister just weeks prior over tensions directly related to the push for independence of Iraq’s oil sector from the U.S.

It appears that the ever-present role of the petrodollar in guiding U.S. policy in the Middle East remains unchanged. The petrodollar has long been a driving factor behind the U.S.’ policy towards Iraq specifically, as one of the key triggers for the 2003 invasion of Iraq was Saddam Hussein’s decision to sell Iraqi oil in Euros opposed to dollars beginning in the year 2000. Just weeks before the invasion began, Hussein boasted that Iraq’s Euro-based oil revenue account was earning a

higher interest rate than it would have been if it had continued to sell its oil in dollars, an apparent signal to other oil exporters that the petrodollar system was only really benefiting the United States at their own expense.

Beyond current efforts to stave off Iraq’s oil independence and keep its oil trade aligned with the U.S., the fact that the U.S. is now seeking to limit China’s ever-growing role in Iraq’s oil sector is also directly related to China’s publicly known efforts to create its own direct competitor to the petrodollar, the petroyuan.

Since 2017, China has made its plans for the petroyuan — a direct competitor to the petrodollar — no secret, particularly after China eclipsed the U.S. as the world’s largest importer of oil. As

CNBC noted at the time:

The new strategy is to enlist the energy markets’ help: Beijing may introduce a new way to price oil in coming months — but unlike the contracts based on the

U.S. dollar that currently dominate global markets, this benchmark would use China’s own currency. If there’s widespread adoption, as the Chinese hope, then that will mark a step toward challenging the greenback’s status as the world’s most powerful currency….The plan is to price oil in

yuan using a gold-backed futures contract in Shanghai, but the road will be long and arduous.”

If the U.S. continues on its current path and pushes Iraq further into the arms of China and other U.S. rival states, it goes without saying that Iraq — now a part of China’s Belt and Road Initiative — may soon favor a petroyuan system over a petrodollar system, particularly as the current U.S. administration threatens to hold Iraq’s central bank account hostage for pursuing policies Washington finds unfavorable.

It could also explain why President Trump is so concerned about China’s growing foothold in Iraq, since it risks causing not only the end of the U.S. military hegemony in the country but could also lead to major trouble for the petrodollar system and the U.S.’ position as a global financial power. Trump’s policy aimed at stopping China and Iraq’s growing ties is clearly having the opposite effect, showing that this administration’s “gangster diplomacy” only serves to make the alternatives offered by countries like China and Russia all the more attractive.

No comments:

Post a Comment