For a few days Princess Latifa had dared to think she could relax. An extraordinary plan to escape from a father she said had once ordered her “constant torture” was looking as if it might work, as she sat on a 30-metre yacht on the Indian Ocean, her home city of Dubai further and further away.

Yet the daughter of Sheikh Mohammed bin Rashid al-Maktoum, the ruler of the glittering Emirati city, still wanted to connect with home, to tell family and friends something of her new-found freedom, sending emails, WhatsApp messages and posting on Instagram from what she thought were two secure, brand new “burner” pay-as-you-go mobile phones.

It was a decision that may have had fateful consequences, according to analysis by the Pegasus project.

At the height of the escape drama, it can now be revealed, the mobile numbers for Latifa and some of her friends back home appeared on a database at the heart of the investigation.

It raises the possibility that a government client of the NSO Group was drawing up possible candidates for some sort of surveillance.

It was late February 2018, and Princess Latifa, then 32, had been desperate to flee her father’s emirate for many years. She had made a “very, very naive” first attempt in 2002, arranging to be driven across the border to neighbouring Oman, but was easily recaptured. This time she hoped it was different, but had prepared for the worst.

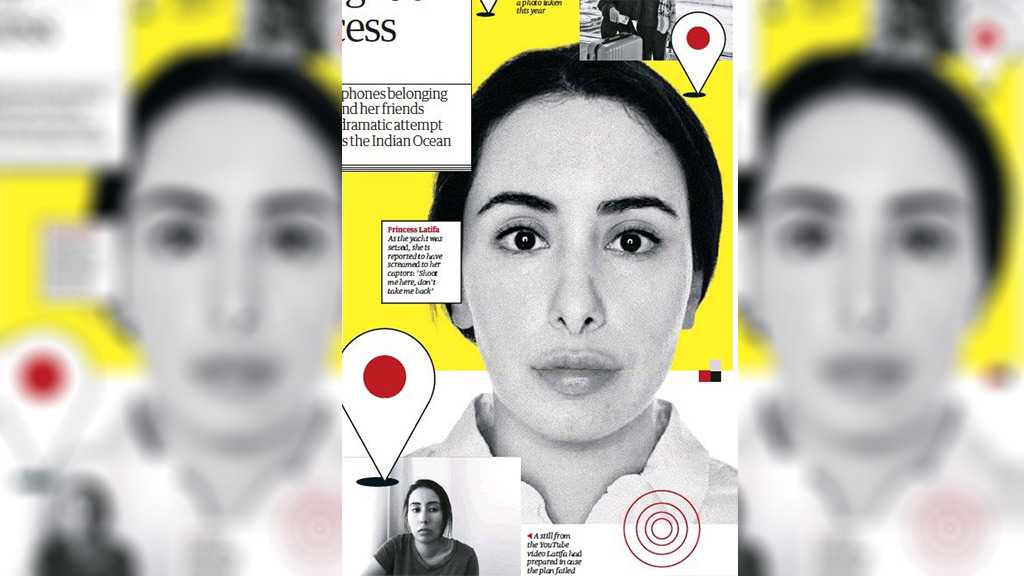

When planning her second escape, Latifa had prepared a video to be released online if the latest effort was foiled, explaining why she wanted to quit home. In it, Latifa described how she was beaten and tortured between 2002 and 2005, during which time she was also forcibly injected with sedatives, and once told by her captors: “Your father told us to beat you until we kill you.”

They were extraordinary claims of abuse that were accepted as truthful in a fact-finding judgment from an English judge, part of a custody battle between Sheikh Mohammed and his sixth and former wife, Princess Haya, over their two young children. Part of that continuing case turns on how Dubai’s ruler treated some of his other children, although after the fact-finding ruling, Sheikh Mohammed insisted it had only told “one side of the story”.

Alongside Latifa on the Nostromo was her best friend and confidant, a Finn with a taste for adventure, Tiina Jauhiainen. She had first met the princess at the end of 2010, when she was asked to become her fitness instructor, and had become so close that the princess asked for her help to get out of the country, in an elaborate scheme worthy of a film.

Also on board was Herve Jaubert, a former French spy, who was captaining the vessel. It was Jaubert who had devised the yacht end of the escape plan after Latifa recruited him – Jauhiainen later told a London court he was paid €350,000 – after she had come across a book he had written about escaping from Dubai, after a business deal he was involved in ran into trouble nearly a decade before.

Latifa and Jauhiainen believed their communications, via the yacht’s satellite uplink, were secure.

They had taken some precautions: Jaubert had turned the ship’s tracking device off and their phones were new, with brand new sim cards.

Latifa and Jauhiainen began their escape at 7am on 24 February from downtown Dubai. The princess’s driver had dropped her off to meet her friend for breakfast, then Latifa changed clothes in the cafe’s bathroom, where she ditched her normal mobile phone, leaving it on silent in the bathroom and went on the run.

Likening themselves to the ill-fated Thelma and Louise, the duo drove six hours to Muscat in neighboring Oman. There with the help of Christian Elombo, a former French soldier and a friend of both women, they made a difficult journey by dinghy and jetski, 13 miles out into the ocean to international waters, where Jaubert and the Nostromo were waiting.

Meanwhile, back in Dubai the hunt for the missing princess had started. A day later, on 25 February, Latifa’s phone appeared in the leaked data list, by Dubai’s doing, it is thought, although not much may have been gleaned, given that it had been left behind in the cafe.

Elombo and his friend, who were supposed to leave Oman, were picked up a day later and questioned by the authorities on behalf of the neighboring state. Realizing contact with Elombo had been lost, and becoming a little more nervous, Latifa and Jauhiainen revised their plan. They had intended to go to Sri Lanka, from where Latifa would fly to the US to claim asylum, but instead they opted to land in India.

Yet, it did not appear to matter much, because for the first four days at sea, until 28 February, there was nobody on their tail. Latifa and Jauhiainen were thrilled to have made it, although conditions were not luxurious: there was an ever-expanding number of cockroaches onboard and, apart from watching a few bad movies, there was not much to do. Inevitably they ended up spending time on their phones.

On the same day, 28 February, the numbers of some of her friends began appearing on the list that is determined to have come from Dubai.

At home, one of Latifa’s few freedoms had been skydiving; she had jumped frequently with Jauhiainen among others. But it was other members of the daredevil club whose numbers were being added to the list in the days that followed, including Juan Mayer, a photographer who regularly took pictures of the princess mid-air, which formed the basis of a short magazine feature.

The data indicates other numbers began to appear too: those of Lynda Bouchiki, an events manager, and, more significantly, Sioned Taylor, a Briton who lived in Dubai, working as a maths teacher in a girls’ school. Taylor, too had been a member of the skydiving club.

Both Bouchiki and Taylor had known Latifa from acting as chaperones prior to her flight. After she had been released from prison, the princess was never allowed out of home unsupervised; friends of the princess say that Taylor, in particular, had also become a close friend.

On the Nostromo, Jauhiainen, who spoke to the Guardian in April, remembers Latifa messaging both Taylor and Bouchiki. The latter did not reply, but she clearly remembers that the princess was chatting with Taylor while they were onboard. At one point Latifa even became suspicious, saying: “I’m not sure this is Sioned,” but the communications continued.

What that signified precisely is unclear, but what the database shows is that Taylor’s mobile phone was listed repeatedly – on 1 and 2 March and again on the day Latifa was to be captured, 4 March. Bouchiki’s number appeared again, on 2 March.

Without forensic examination of phones, it is not possible to say whether any attempt was made to infect the devices, or whether any infection attempt was successful.

But at sea, the situation had changed, ominously. Jaubert says it was on 1 March, a day after Latifa’s friends and family were first targeted that he first noticed the first ship following the Nostromo, curiously taking the same route and following at the same speed. Spotter planes followed soon after that.

It was clear they had been picked up by the Indian coastguard. The captain became increasingly nervous, also emailing a campaign group, Detained in Dubai, worrying that he might run out of fuel as he chose to head towards the Indian port city of Goa, and seeking their help. But they were never to arrive.

After 10pm on 4 March, about 30 miles offshore, in an operation authorized by the prime minister, Narendra Modi, at the request of Dubai, around 15 Indian commandos in “full military gear” stormed the yacht, firing stun grenades to incapacitate those onboard.

Latifa and Jauhiainen panicked, running below deck and locking themselves in the bathroom in a desperate attempt not to be seized. Latifa frantically rang Radha Stirling from Detained in Dubai, who said the princess was “frightened, hiding, that there were men outside and that she heard gunfire” on the emergency call.

But the two women had to give themselves up, as smoke poured in through the bathroom vents. They were captured and dragged to the deck, and according to Jauhiainen, Latifa was screaming, in English: “Shoot me here, don’t take me back” as she was dragged off, handed over to waiting Emirati forces, tranquillized and returned to Dubai.

Dubai did not respond to a request for comment. Sheikh Mohammed did not respond, although it is understood he denies having attempted to hack the phones of Latifa or her friends or associates, or ordering others to do so. He has also previously said he feared Latifa was a victim of a kidnapping and that he had conducted “a rescue mission”.

NSO denies the leaked list of numbers is that of “Pegasus targets or potential targets” and says the numbers are not related to the company in any way. Claiming that a name on the list is “is necessarily related to a Pegasus target or potential target is erroneous and false”.

Jauhiainen and Jaubert were released after a short period of detention, with the Finn relocating to London. Latifa was held under house arrest back home, and after a while managed to smuggle out fresh videos to Jauhiainen to tell more about her plight. “I’m a hostage. I am not free. I’m enslaved in this jail,” she angrily said.

But in the past three months there has been a notable change, involving two of the women Latifa tried to message from the boat. In May, Taylor posted a picture on Instagram of Latifa, sitting in a Dubai shopping mall, with her and Bouchiki, to show she was enjoying a degree of freedom at home.

Then, in June a picture followed of Latifa inside Madrid’s main airport, indicating she had been able to travel abroad. “I hope now that I can live my life in peace without further media scrutiny,” the princess said in a statement released by her lawyers, suggesting after the years of conflict some sort of accommodation with her father had been reached.

With the passage of time, it may never be possible to establish definitively how Latifa was recaptured at gunpoint.

NSO said that the fact that a number appeared on the list was in no way indicative of whether that number was selected for surveillance using Pegasus.

No comments:

Post a Comment