The following is the English translation from Arabic of the latest article by Turkish career journalist Husni Mahali he published in the Lebanese Al-Mayadeen news site Al-Mayadeen Net:

After Turkey has become a main party in the overall developments of the Syrian file with the years of the so-called ‘Arab Spring’, Ankara has developed many scenarios and calculations for its future relations with Damascus, and through it with the rest of the region, especially Iraq which is bordering Turkey, Syria, and Iran.

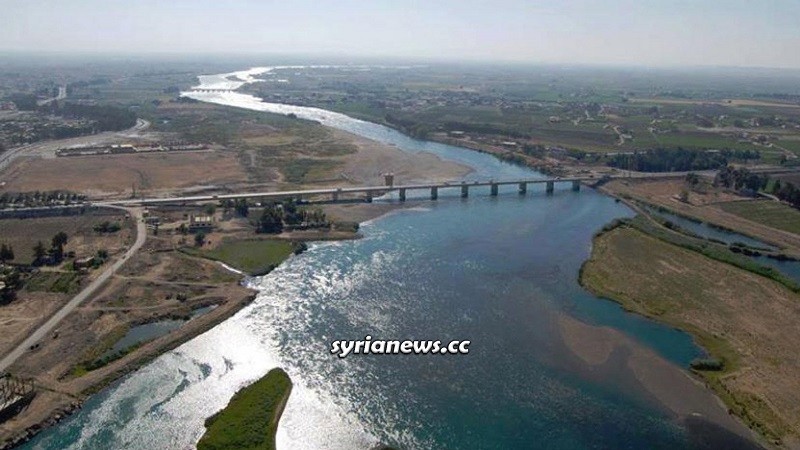

The waters of the Euphrates, Tigris and other small rivers (about 12 rivers with Syria and 3 with Iraq) come within these calculations, especially with the continuing dry seasons, which seem to be reflected in one way or another on Ankara’s water policies in the future with the two mentioned countries.

The water of the Euphrates has always been an important material in Turkish bargaining with Syria and Iraq, together or separately since Turkey began building dams on the Euphrates River, the first of which was the Kaban Dam which was inaugurated in 1974, and then the Karakaya Dam in 1987. The Ataturk Dam, which was inaugurated in 1991 was the most important in the water crisis between Turkey and both Syria and Iraq, especially after Prime Minister Suleiman Demirel said in 1991 ‘The Arab countries sell their oil, so why we do not sell our water also?’.

Ankara has insisted from the beginning on building dams after it refused to sign the international agreement (1997) that regulates the joint use of shared international water, including the Nile, the Euphrates and the Tigris, and it says that the last two are Turkish rivers crossing the border and they are not two shared rivers and that it has the right to dispose of its waters as it wishes, taking into account the interests of the downstream countries.

The roots of the Turkish water crisis with Syria and Iraq go back to the year 1920 when ‘tripartite and bilateral’ agreements were signed between Turkey and both Syria (a French colony) and Iraq (a British colony) to divide the water according to international standards followed at the time. The ‘Lausanne’ agreement (1923) by which Western countries recognized the modern Turkish republic, the heir to the Ottoman Empire, included a clause regarding the Tigris and Euphrates rivers, stating: “No country from these three countries has the right to build a dam or a reservoir or divert a river course without coordinating with other countries to ensure that their interests are not harmed.’

With the independence of Syria and Iraq, water remained a fundamental problem hindering the establishment of lasting friendly relations between the three countries, which has enough other problems that prevented them from developing relations between them, with the Syrian and Iraqi doubts always regarding the possibility that the Turkish side would use water as a weapon against them.

The documents of the US embassy in Tehran (November 4, 1979) indicated that “the CIA proposed to the Director General of the National Water Corporation, Suleiman Demirel in the year 1955-1956, to build large dams on the Euphrates, to be a weapon in Ankara’s hand against Syria, whose relations were bad at that time with Turkey.’

This explains the failure of the agreement signed by President Turgut Ozal in 1987 with the late President Hafez al-Assad, after it was affected by the tensions in the relations between the two countries, due to Ankara’s accusation of Damascus of supporting the PKK, if we ignore the psychological-influencing issue of the Iskenderun Strip.

According to the 1987 agreement, the Turkish side pledged to leave 500 cubic meters per second of the Euphrates water for Syria (42%) and Iraq (58%), provided that this amount would increase to reach 650 cubic meters after 5 years, in exchange for Damascus giving up this support, without this agreement preventing Ankara from building the dams of Perajik (50 km from the border with Syria) and Qaraqamish (3 km from the Syrian border) and two dams on the Tigris River, while the National Water Corporation plans to build a total of 22 dams on the two mentioned rivers, to reach the amount of the water that will be stored in these dams amounts to about 140 billion cubic meters.

Ankara plans to irrigate 1.8 million hectares of agricultural land with this water, and it also aims to generate 27 billion kilowatt hours of electricity (23% of Turkey’s consumption) from these dams, in addition to about 750 dams of various sizes (550 of which are large dams) built by Turkey on dozens of small and large rivers, the length of which exceeds 20 thousand km inside the Turkish borders.

President Erdogan’s statements last week in which when he said, “Turkey is not rich in water, as some believe,” raised many questions about the possibilities of using water as a weapon in Ankara’s potential bargains with Syria and Iraq, and most importantly with the “SDF” and the Kurdish People’s Protection Units that control the East of the Euphrates with the support of Washington, which Ankara fears that it seeks to establish an independent Kurdish entity in the region as is the case in northern Iraq.

Official Turkish circles develop many scenarios regarding water policies that include serious studies about water sources, including rain and groundwater, in addition to the mentioned rivers, which number more than 100.

These studies estimate the total capacity of surface (rain) and groundwater that can be utilized at about 115 billion cubic meters, of which about 60 billion cubic meters are used annually. These figures prompted Ankara to implement many projects to build underground dams, a new technology that contributes to storing groundwater as is the case in the rivers on which Ankara builds its dams.

These accounts did not prevent Ankara from continuing to build hundreds of dams on dozens of rivers that flow into its lands and flow into the seas (Aegean, Mediterranean, Marmara and Black), or leave it to other neighboring countries, including Iran, Georgia, Armenia, Bulgaria and Greece, or come from these countries, in. At the time when Turkey succeeded in laying the pipeline (80 km) that carries water under the sea (75 million cubic meters annually) to Turkish northern Cyprus with plans to sell this water to the Greek Cypriots, and even to ‘Israel’, the late President Turgut Ozal failed in his water pipeline project to ‘Israel’ through Syria and Lebanon, and another pipeline extending to the Gulf countries via Jordan to sell the water of the Saihan and Caihan rivers to these countries.

Many academic studies in the West see the Turkish datum as a sufficient reason for both Iraq and Syria to fear about the possible repercussions of Ankara’s policies with the two countries mentioned with the Kurdish element in them, everyone knows that Ankara’s implementation of its projects on the Euphrates, Tigris and other small rivers will put Iraq and Syria in front of serious challenges that will be cause serious implications for agriculture, food security, drinking water and energy generation, especially with the environmental fluctuations that threaten of drought years, according to all scientific studies worldwide.

As Ankara continues its current policies in Syria and Iraq, it has become clear that sooner or later it will use water as an influential card in its bargaining with Damascus, Baghdad and the Kurds, who are the primary beneficiaries of the waters of the Euphrates, the Tigris and other small rivers, given that the Syrian dams are in the “SDF”. This explains the presence of Ankara in Afrin (Afrin River) west of the Euphrates in general, in addition to the area extending from Ras al-Ain to Tal Abyad, where many of the small Turkish rivers enter Syria, without ignoring their presence in Jarablus, the entrance to the Euphrates into Syria, and its attempt to control Ayn al-Arab (Kobane), which is on the eastern bank of the river, similarly is the case in northern Iraq, as Turkey succeeded in establishing many military bases in the strategic mountains overlooking or near the waterways, including the Tigris and the Great Zab.

The bet or hope remains in the possibilities of returning to friendly relations between Ankara and each of Damascus and Baghdad, and even Iran, which is also a party to the water issue, especially with Iraq, after Ankara succeeded after 2003 in establishing friendly relations with Syria, Iraq, Iran and the rest of the countries of the region; President Erdogan, and before him President Abdullah Gul, announced more than once that “there is no longer a so-called water problem with the two aforementioned neighbors so that Mesopotamia will return again as the cradle of the civilizations that lived in it thousands of years ago.” This is what has been blown in the wind and the feelings of brotherhood and friendship between Ankara and both Baghdad and Damascus have become forgotten, after the policies of “zeroing problems with neighbors” succeeded in “zeroing the neighbors”, and water will soon be their most difficult concern!

To help us continue please visit the Donate page to donate or learn how you can help us with no cost on you.

Follow us on Telegram: http://t.me/syupdates link will open Telegram app.

بعد إدلب والكرد.. ماذا عن الفرات ودجلة؟

4 شباط

تضع الأوساط التركية الرسمية العديد من السيناريوهات في ما يتعلق بالسياسات المائية التي تتضمّن دراسات جدية حول مصادر المياه، ومنها الأمطار والمياه الجوفية، إضافةً إلى الأنهار المذكورة التي يزيد عددها على 100 نهر.

بعد أن أصبحت تركيا طرفاً أساسياً في مجمل تطورات الملف السوري مع سنوات ما يسمى بـ”الربيع العربي”، وضعت أنقرة العديد من السيناريوهات والحسابات لعلاقاتها المستقبلية مع دمشق، وعبرها مع باقي دول المنطقة، وفي مقدمتها العراق المجاور لتركيا وسوريا وإيران.

وتأتي مياه الفرات ودجلة والأنهار الصغيرة الأخرى (حوالى 12 نهراً مع سوريا و3 مع العراق) ضمن هذه الحسابات، وخصوصاً مع استمرار مواسم الجفاف التي يبدو أنها ستنعكس بشكل أو بآخر على سياسات أنقرة المائية مستقبلاً مع الدولتين المذكورتين.

وكانت مياه الفرات دائماً مادة مهمة في المساومات التركية مع سوريا والعراق معاً أو على انفراد، منذ أن بدأت تركيا ببناء السّدود على نهر الفرات، وأولها سدّ كابان الذي تمّ افتتاحه في العام 1974، ثم سدّ كاراكايا في العام 1987. وكان سدّ أتاتورك الذي تمّ افتتاحه في العام 1991 هو الأهم في أزمة المياه بين تركيا وكل من سوريا والعراق، وخصوصاً بعد أن قال رئيس الوزراء سليمان ديمريل في العام 1991 “إن الدول العربية تبيع نفطها، فلماذا لا نبيع أيضاً مياهنا؟”.

وقد أصرّت أنقرة منذ البداية على بناء السّدود بعد أن رفضت التوقيع على الاتفاقية الدولية (1997) التي تنظم عملية الاستخدام المشترك لمياه المجاري الدولية المشتركة، ومنها النيل والفرات ودجلة، وهي تقول إنّ الأخيرين نهران تركيان عابران للحدود، وليسا نهرين مشتركين، ومن حقّها التصرف بمياهها كما تشاء، مع مراعاة مصالح دول المصب.

تعود جذور أزمة المياه التركية مع سوريا والعراق إلى العام 1920، عندما تم التوقيع على اتفاقيات “ثلاثية وثنائية” بين وتركيا وكل من سوريا (مستعمرة فرنسية) والعراق (مستعمرة بريطانية) لتقسيم المياه وفق المعايير الدولية المتبعة آنذاك. وتضمّنت اتفاقية “لوزان” (1923) التي اعترفت الدّول الغربية بموجبها بالجمهورية التركية الحديثة، وريثة الدولة العثمانية، بنداً خاصاً بنهري دجلة والفرات جاء فيه: “لا يحق لأية دولة من هذه الدول الثلاث إقامة سد أو خزان أو تحويل مجرى نهر من دون أن تنسق مع الدول الأخرى لضمان عدم إلحاق الأذى بمصالحها”.

ومع استقلال سوريا والعراق، بقيت المياه مشكلة أساسية تعرقل إقامة علاقات ودية دائمة بين الدول الثلاث التي لديها ما يكفيها من المشاكل الأخرى التي منعتها من تطوير العلاقات في ما بينها، مع استمرار الشكوك السورية والعراقية دائماً باحتمالات أن يستخدم الجانب التركي المياه كسلاح ضدها.

وقد بيّنت وثائق السفارة الأميركية في طهران (4 تشرين الثاني/نوفمبر 1979) “أن المخابرات الأميركية CIA اقترحت على مدير عام مؤسسة المياه الوطنية سليمان ديميريل في العام 1955-1956 بناء سدود كبيرة على الفرات، لتكون سلاحاً بيد أنقرة ضد سوريا التي كانت علاقاتها سيئة آنذاك مع تركيا”.

ويفسر ذلك فشل الاتفاقية التي وقع عليها الرئيس تورغوت أوزال في العام 1987 مع الرئيس الراحل حافظ الأسد، بعد أن تأثرت بالتوترات التي شهدتها العلاقات بين البلدين، بسبب اتهام أنقرة لدمشق بدعم حزب العمال الكردستاني، إذا ما تجاهلنا قضية لواء الإسكندرون ذات التأثير النفسيّ.

وقد تعهّد الجانب التركي وفق اتفاقيّة 1987 بترك 500 متر مكعب في الثانية من مياه الفرات لكل من سوريا (42%) والعراق (58%)، على أن تزداد هذه الكمية لتصل بعد 5 سنوات إلى 650 متراً مكعباً، مقابل تخلي دمشق عن هذا الدعم، من دون أن تمنع هذه الاتفاقية أنقرة من بناء سدي بيراجيك (50 كم عن الحدود مع سوريا) وقرقميش (على بعد 3 كم من الحدود السورية) وسدين على نهر دجلة، فيما تخطط مؤسسة المياه الوطنية لبناء ما مجموعه 22 سداً على النهرين المذكورين، لتصل كمية المياه التي سيتم تخزينها في هذه السدود إلى حوالى 140 مليار متر مكعب.

وتخطّط أنقرة لريّ 1.8 مليون هكتار من الأراضي الزراعية بهذه المياه، كما تهدف إلى توليد 27 مليار كيلو واط /ساعة من الكهرباء (23% من استهلاك تركيا) من هذه السدود، إضافةً إلى حوالى 750 سداً بمختلف الأحجام (550 منها سد كبير) بنتها تركيا على عشرات الأنهار الصغيرة والكبيرة، ويزيد طولها داخل الحدود التركية على 20 ألف كم.

وجاءت أقوال الرئيس إردوغان الأسبوع الماضي، إذ قال “إن تركيا ليست غنية بالمياه، كما يعتقد البعض”، لتثير العديد من التساؤلات حول احتمالات استخدام المياه كسلاح في مساومات أنقرة المحتملة مع سوريا والعراق، والأهمّ مع “قسد” ووحدات حماية الشعب الكردية التي تسيطر على شرق الفرات بدعم من واشنطن، التي تتخوّف أنقرة من أن تسعى إلى إقامة كيان كردي مستقل في المنطقة، كما هو الحال في الشمال العراقي.

وتضع الأوساط التركية الرسمية العديد من السيناريوهات في ما يتعلق بالسياسات المائية التي تتضمّن دراسات جدية حول مصادر المياه، ومنها الأمطار والمياه الجوفية، إضافةً إلى الأنهار المذكورة التي يزيد عددها على 100 نهر.

وتقدّر هذه الدراسات الطاقة الإجمالية للمياه السطحية (الأمطار) والجوفية التي يمكن الاستفادة منها بحوالى 115 مليار متر مكعب، يتم استغلال حوالى 60 مليار متر مكعب منها سنوياً. ودفعت هذه الأرقام أنقرة إلى تنفيذ العديد من المشاريع لبناء السدود الجوفية، وهي تقنية جديدة تساهم في تخزين المياه الجوفية، كما هو الحال في الأنهار التي تبني عليها أنقرة سدودها.

ولم تمنع هذه الحسابات أنقرة من الاستمرار في بناء مئات السدود على عشرات الأنهار التي تنبع في أراضيها وتصب في البحار (إيجة والأبيض المتوسط ومرمرة والأسود)، أو تغادرها إلى دول مجاورة أخرى، ومنها إيران وجورجيا وأرمينيا وبلغاريا واليونان، أو تأتيها من هذه الدول، في الوقت الذي نجحت تركيا في مد الأنبوب (80 كم) الذي ينقل المياه تحت البحر (75 مليون متر مكعب سنوياً) إلى شمال قبرص التركية مع حسابات لبيع هذه المياه للقبارصة اليونانيين، وحتى “إسرائيل”، فقد فشل الرئيس الراحل تورغوت أوزال في مشروعه لمد أنابيب المياه إلى “إسرائيل” مروراً بسوريا ولبنان، وأنبوب آخر يمتد إلى دول الخليج عبر الأردن لبيع مياه نهري سايهان وجايهان لهذه الدول.

وترى العديد من الدراسات الأكاديمية في الغرب في المعطيات التركية سبباً كافياً لتخوّف كل من العراق وسوريا من الانعكاسات المحتملة لسياسات أنقرة مع الدولتين المذكورتين بالعنصر الكردي فيهما، فالجميع يعرف أن تنفيذ أنقرة مشاريعها على نهري الفرات ودجلة والأنهار الصغيرة الأخرى سيضع العراق وسوريا أمام تحديات جدية ستكون لها انعكاسات خطيرة على الزراعة والأمن الغذائي ومياه الشرب وتوليد الطاقة، وخصوصاً مع التقلبات البيئية التي تهدد بسنوات الجفاف، وفق كل الدراسات العلمية عالمياً.

ومع استمرار أنقرة في سياساتها الحالية في سوريا والعراق، بات واضحاً أنها، عاجلاً أم آجلاً، ستستخدم المياه كورقة مؤثرة في مساوماتها مع دمشق وبغداد والكرد، المستفيد الأول من مياه الفرات ودجلة وباقي الأنهار الصغيرة، باعتبار أن السدود السورية في “قسد”. ويفسر ذلك تواجد أنقرة في عفرين (نهر عفرين) غرب الفرات عموماً، إضافةً إلى المنطقة الممتدة من رأس العين إلى تل أبيض، حيث العديد من الأنهار التركية الصغيرة التي تدخل منها إلى سوريا، من دون أن نتجاهل تواجدها في جرابلس، مدخل الفرات إلى سوريا، ومحاولتها السيطرة على عين العرب (كوباني)، وهي على الضفة الشرقية للنهر، وهو الحال في شمال العراق، إذ نجحت تركيا في إقامة العديد من القواعد العسكرية في الجبال الاستراتيجية المطلة أو القريبة من المجاري المائية، ومنها دجلة والزاب الكبير.

ويبقى الرهان أو الأمل في احتمالات العودة إلى علاقات الصداقة بين أنقرة وكل من دمشق وبغداد، وحتى إيران، وهي أيضاً طرف في قضية المياه، وخصوصاً مع العراق، فبعد أن نجحت أنقرة بعد العام 2003 في إقامات علاقات ودية مع سوريا والعراق وإيران وباقي دول المنطقة، أعلن الرئيس إردوغان، وقبله الرئيس عبد الله جول، أكثر من مرة، أنه “لم تعد هناك ما يسمى بمشكلة المياه مع الجارتين المذكورتين، ليعود ما بين النهرين من جديد مهداً للحضارات التي عاشت فيها قبل آلاف السنين”، وهو الكلام الذي أصبح في مهب الريح، كما أصبحت مشاعر الأخوة والصداقة بين أنقرة وكل من بغداد ودمشق في ذاكرة النسيان، بعد أن نجحت سياسات “تصفير المشاكل مع الجيران” في “تصفير الجيران”، وستكون المياه قريباً همها الأصعب!

فيديوات ذات صلة

مقالات ذات صلة

No comments:

Post a Comment