By Miko Peled

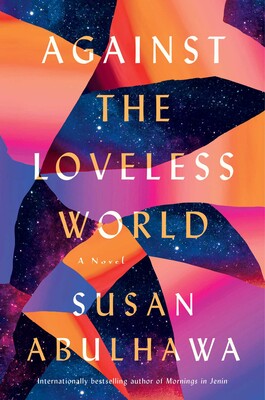

Writer and political activist Susan Abulhawa weaves a daring tale of a Palestinian woman’s defiant experience in solitary confinement at an Israeli prison.

Book Review — “I don’t care to be accommodating,” Nahr, the lead character in Susan Abulhawa’s new novel, “Against the Loveless World,” tells us. Perhaps she says this to prepare us or even warn us of what lies ahead. Either way, the statement runs like a thread throughout the entire book.

As the pages of the novel turn and the story of Nahr’s life unfolds, we go through the ups and downs of this Palestinian woman’s unpredictable life. Slowly, as we are gripped by the power of her story, we come to realize that Nahr’s unwillingness to be accommodating is admirable but comes at a heavy price.

Susan Abulhawa is the author of the international bestseller, “Mornings in Jenin,” among other important works of prose and poetry. Personally, I found her newest novel to be daring, honest, and totally unaccommodating. Abulhawa is also a friend of mine, and reading her novel felt a lot like listening to her talk.

A cube

Nahr is an inmate held in solitary confinement at an Israeli prison and she tells us the story from her tiny cell. This is no ordinary cell, the Israeli authorities placed Nahr in a highly sophisticated cell where everything is automated: the light and the shower turn on and off on their own; the toilet flushes at set times and Nahr the inmate needs to accommodate herself to their schedule. She lives in this cell and is unable to tell if it is day or night or what time of day it is.

For reasons that she lays out in the story, Nahr is not permitted to have visitors of her choice but from time to time an international observer, a journalist, or a prison guard come into the cell. It is during these random visits that we see Nahr expressing her unwillingness to be accommodating for the first time.

Tatreez

I can’t decide which metaphor better describes Nahr’s story, so I will use two. The first is a piece of Tatreez, or Palestinian embroidery. The characters in the story are the colors and designs that represent the various towns, villages, and regions of Palestine. It is embroidered over a black cloth, which is Palestine, thus displaying both the immense beauty and unspeakable tragedy of Palestine.

The other metaphor is a cluster of vines that twist and grow around the trunk of a large tree. In Palestine, one sees this often. They are particularly beautiful when they are in full bloom, wrapped around large trunks of tall trees. The stories of Nahr and the people around her are the vines wrapping around Palestine.

Nahr is surrounded by several strong characters, many of whom represent the breadth of the Palestinian experience. Their stories are told through Nahr’s story and together they evoke the powerful emotions that we experience together with her: innocence, passion, love, and hate, sadness and anger as well as delicately threaded tenderness, yearning, and even compassion. Abulhawa seamlessly weaves Nahr’s personal story and the stories of the other characters into the greater story of Palestine.

The story takes us into two of the largest Palestinian refugee communities in the world, Kuwait and Jordan. We come face to face with Palestinians who became refugees in 1948, and then again in 1967, and then brutally kicked out of Kuwait and turned into refugees again as a result of the first Gulf War. Each time they think they can finally rest, something happens and they are forced to move again. Yet throughout this painful and seemingly endless odyssey their anchor continues to be Palestine.

A story of love

Nahr experiences the full scope of cruelty meted out to women by men, by the patriarchy. Since men’s brutality towards women is not unique to a particular race, nationality, or culture, her experience is universal. And yet, although she suffers greatly at the hands of men, she is capable of feeling and expressing a deep, sincere love for a man.

Though she speaks to us from a cold, lonely cell in which she is held by Israel, Nahr is able to relay her feelings to one man who she truly loves and who loves her completely. She admits to “a sexual yearning made insatiable by love so vast, as if a sky.”

Though she speaks to us from a cold, lonely cell in which she is held by Israel, Nahr is able to relay her feelings to one man who she truly loves and who loves her completely. She admits to “a sexual yearning made insatiable by love so vast, as if a sky.”

In one scene Nahr watches the man she loves and describes what she sees, “the guilt, the impotence of seeing those settlements, the anguish over his brother, his mother, the years in prison, the torture, the inability to move.” Then, reflecting on her own sense of helplessness she says, “I wanted to take him in my arms and fix everything,” but, Nahr sums it up “all I could do was help carry the tea glasses.”

Palestine, for those who were torn away from her and for those who care for her, is like a loved one dying of terminal cancer. Hard as we may try, all we can do is watch as she is being eaten away by the cancer of Zionist brutality, and make her as comfortable as possible as she slips away.

Nahr’s pain is deep and real and reading this novel one often forgets that it is, in fact, fiction. She experiences pain as a woman, as a Palestinian, and as a human being. In Nahr’s own words, it is “a cloistered, unreachable, immutable ache.”

The spirit of resistance

Nahr tells us about “the epic fabrication of a Jewish nation returning to its homeland.” She goes on to say that the deceit, “had grown into a living, breathing narrative that shaped lives as if it were truth.”

She describes the Jewish-only settlements that she sees spreading all over Palestine. Entire cities, neighborhoods, and homes of people she knows and loves who were forced to flee their homeland, taken over by Jewish settlers. She describes the silences of older Palestinians who cannot bear to talk about their loss.

But the spirit of resistance is alive in Palestine and Nahr will not stand idly by as others prepare to act. Nahr is enraged by the ruthlessness of settlers and soldiers, tucked away safely in their exclusive, Arab-free colonies. They live on stolen Palestinian land and come out periodically to attack Palestinians with impunity.

Once she realizes that people around her are engaged in acts of resistance, she wants in on the action. Here, once again, we see Nahr unaccommodating, fierce, and willing to face the consequences.

From her solitary cell in an Israeli prison, Nahr recalls Ghassan Kanafani and James Baldwin, two great writers, who, like her, were unwilling to be accommodating. They suffered greatly because of who they were, one a Palestinian, the other a Black American. They both wrote and spoke with unmatched courage and clarity, and although dead for decades, (Kanafani was murdered by Israel in 1972, Baldwin died of cancer in 1987), they remain icons of the struggle against racism, oppression, and colonialism.

Feeling the pulse

Along with Ghassan Kanafani and Ibrahim Nasrallah, Susan Abulhawa’s writing has the rare quality of allowing us to taste the flavor, to smell the fragrance, and to feel the pulse of Palestine. A true understanding of the Palestinian experience is not possible without reading the work of these three writers.

No comments:

Post a Comment