By Clinton Nzala

BAMAKO, MALI — On the 8th of October, Choguel Maïga, the prime minister of Mali, boldly informed the world that its former colonial power, France, was sponsoring terrorists in the country’s northern region. Standing before dozens of cameras and microphones, he provided details on how the French army had established an enclave in the northern town of Tidal and handed it over to well-known terrorist groups. The revelation was shocking not simply for the serious nature of the accusation but because in past times West African leaders have rarely sparred so openly with the French government. A chain of events simmering in the background for weeks triggered the latest spat.

On October 2nd, Britain’s BBC published an article with the headline “Mali’s plan for Russia mercenaries to replace French troops unsettles Sahel.” The embattled media outlet further claimed: “There is deep international concern over Mali’s discussions with the controversial Russian private military company, the Wagner Group.”

By now we all understand that whenever Western corporate media outlets utter the expression “international community,” they are referring simply to the U.S. and its European buddies, such as France. Case in point, in Addis Ababa, the seat of the African Union, or at the headquarters of the Economic Community for West African States (ECOWAS), there was absolutely no concern about Mali’s discussions with the Wagner Group. Even in Mali, the majority of citizens and political actors welcomed the possibility of the Russian security firm joining the fight against terrorist groups in the north. Why? Well, Malians believe the Wagner Group to be significantly more neutral than France, a country they accuse of having its own political and economic interests in the conflict.

L’habit ne fait pas le moine (the vestment doesn’t make the monk)

Anti-French protests have not been in short supply in Mali over the past few years, a sign of the citizens’ displeasure with the presence of foreign troops in their country. A segment of society has gone as far as describing the situation as an occupation. For this reason the only place of concern for replacing the French military with a Russian security firm was in Paris. But why? Why would the French government be worried about the possibility of the Wagner Group joining the fight against terrorist groups in the Sahel? If France were indeed concerned about defeating these armed groups, then their government should have been happy to receive news that more hands will soon join the battle, especially those belonging to a military firm experienced in conducting anti-terror operations.

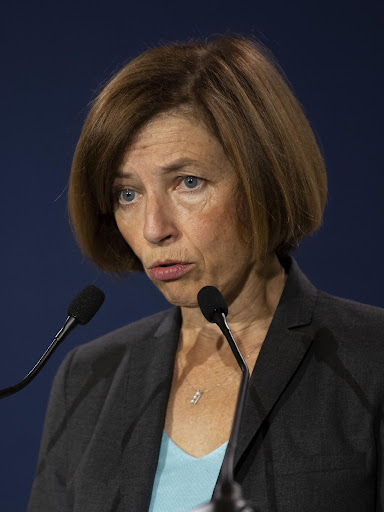

France instead threw a tantrum, tossing all of their toys out of their coats. French officials threatened to withdraw their troops from the region and cease providing aid to Mali’s armed forces. Florence Parly, France’s current Minister of the Armed Forces and a former member of the Socialist Party, arrogantly told reporters that her country will not “cohabit with Russian mercenaries.” Well, someone needs to tell the minister that in Africa guests don’t get to decide who they share the house with; only the host is reserved such rights.

It is not difficult to understand why France would react in such a manner. In my village on the banks of Africa’s longest river, the Zambezi, we say, “Only a witch is unsettled by the arrival of a witch-finder in the village.”

If I said I was surprised by France’s reaction, I would be lying. The average African is well aware that France’s so called fight against “terrorism” in the Sahel has nothing to do with protecting the lives of the people of the region but everything to do with protecting its interests. Those interests date back to the dark period when the region was ruled with an iron fist from Paris. Only naivety would permit someone to believe that the French government would fork out billions of francs and risk the lives of its citizens to protect the lives of Black people thousands of miles away.

Florence Parly. | Wikimedia Commons

Rights denied from Paris to Marseilles and beyond

If France is in love with Africans, why don’t they first express their affection to the French citizens of African descent? Twenty-one years into the new millennium, Black people living in France continue to be treated as second-class citizens. More often than not, these souls are compiled into squalid living conditions in the ghettos of Paris or Marseille, with little or no social services provided to them, and are subjected to racism and harassment by security agents for no reason other than not looking “French enough.” How about first assisting those Africans in Libya who are being held as slaves in torture hellholes run by armed bandits funded by the European Union?

What about France repaying Haiti for forcing the small Caribbean country to reimburse its former slaveholding settlers and their descendants following the Haitian revolution. That total amount was not repaid until 1947 and, in present-day value, amounts to over $28 billion, according to French economist Thomas Piketty, or upwards of $260 billion if a 3 percent annual interest rate were applied. In 2015, just prior to his trip to Haiti, the French president said, “When I come to Haiti, I will, for my part, settle the debt that we have.” Aides scurried to clarify that the debt in question was not monetary but “moral.” In the relationship between France and Haiti, however, neither debt has been settled.

As far as Mali is concerned, France will not play fair because Paris’s only concern is that the arrival of other actors in the African country will dilute its own influence and the monopoly French companies enjoy in the region. All other Africans and their descendants affected by the French colonial and neo-colonial project must fend for themselves.

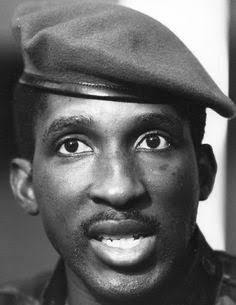

France’s fit also shows the deeply ingrained colonial hangover it continues to suffer several decades after losing its colonies in West Africa. Paris arrogantly and abhorrently still views itself as the landlord and self-appointed sheriff of West Africa; therefore, any other party that wishes to venture into the region must seek its permission and blessings, a mentality that in the last five decades has led to a lot of bloodshed and atrocities committed by France’s stooges in its former colonies. These tragedies include the brutal murder of Pan-Africanist revolutionary heroes such as Thomas Sankara and other leaders who signed their death certificates by simply refusing to bow down at the throne of French imperialism.

A very troubled history in Africa

France’s role in overthrowing African leaders and replacing them with dictators, such as Gabon’s Omar Bongo, is well documented. This started with the first military intervention into Gabon in 1964, when French paratroopers flew in to help then-President Leon Mba to brutally crush an attempted overthrow by a group of young military officers. These soldiers had briefly seized power in response to growing public dissatisfaction with Mba’s leadership. During the next four decades, France would go on to directly or indirectly participate in the toppling or installing of governments in different African countries such as Niger, Chad, Ivory Coast, Burkina Faso, Central African Republic and the Democratic Republic of Congo, among many others. Paris even deployed troops to Rwanda in 1994 as part of Operation Turquoise, which provided support to Hutu government forces during the genocide in the small African country. Once establishing a control zone, French military officials allowed Radio Télevision Libre des Milles Collines to broadcast from Gisenyi. One radio show encouraged “Hutu girls to wash yourselves and put on a good dress to welcome our French allies. The Tutsi girls are all dead, so you have your chance.”

Successive French governments have often claimed that these interventions were done to maintain or stabilize democracy. However, if France’s past and current allies are anything to go by, this claim is outright laughable. The list of Paris’s choice of friends in Africa is littered with brutal and corrupt dictators such as Blaise Compaore (Burkina Faso), Mobutu Sese Seko (Democratic Republic of the Congo) and Omar Bongo (Gabon), individuals who not only bled their country’s coffers dry but committed unimaginable human rights atrocities right under the nose, or with the explicit blessing, of the French government.

France’s two-faced foreign policy in West Africa was further exposed in February 1996, when Niger’s first democratically elected government was overthrown by the military. Instead of throwing its support behind ousted president Mahamane Ousmane, officials in Paris opted to watch from the sidelines despite having a military base in the country. Deciding to stand idly by was viewed as a nod of approval for the coup.

The same France that claims to be in Africa to ensure the “natives” can fully enjoy the benefits of Western democracy, on two occasions in the 1990s ordered its troops stationed in Gabon to join Omar Bongo’s troops to violently crush pro-democracy demonstrators. In this case, thousands had taken to the streets to protest against the results of a disputed election. Paris also continues to hobnob with autocrats such as Cameroon’s Paul Biya, who has turned the country into a personal fiefdom that he has ruled with an iron fist since 1982.

As the self-appointed enforcer of democracy in Africa, France certainly has a strange choice of bedfellows. Going by the long list of Paris’s shady activities in the region, how can claims made by the government of Mali, that France is sponsoring and arming terrorist groups, effectively destabilizing the region, be dismissed? Instead of issuing threats, the best way the French government can clear its name is by being more transparent with its activities in the Sahel. Paris should also understand that regional and continental organizations such as the African Union and ECOWAS are capable of dealing with the conflict in the Sahel.

Taking care of business

Despite the misgivings some outsiders might have against African organizations in resolving internal conflicts, the African Union Mission in Somalia has unequivocally demonstrated its capabilities against Al Shabaab. Meanwhile, the Southern African Development Community (SADC) standby forces — led by Rwanda, Botswana and South Africa — have produced even better results in battling insurgents in Mozambique’s Cabo Delgado region. These achievements have been made with less than 10 percent of the resources that Paris has spent in the Sahel conflict with absolutely no results to speak of.

It is long overdue that the world accepts the fact that Africans are capable of solving their own problems.

Conclusion

The situation in the Sahel region remains a source of concern and requires long-lasting solutions. Those solutions, however, must derive from the streets of Addis Ababa, Bamako, Nouakchott, N’Djamena and Dakar, not from the government corridors and suburbs of Paris or Brussels. The quarrel between Bamako and Paris should serve as an eye-opener to the latter, that the age of barking orders to former colonies is over, fini.

France must now come to the realization that while the older generation of Africans might have been pliable to its machinations in the region, it is now dealing with a new generation of Africans, people unwilling to bow down passively to a former imperial power. It’s a generation that won’t allow the West or another power to choose their enemies or friends.

“Everything must change,” sang the late and legendary South African trumpeter, composer and singer, Hugh Masekela, in his hit song called “Change.” The time of change in how West Africa conducts its affairs has also come and, while the process of change can be painful and uncertain, it is inevitable.

Reexamining and recalibrating its foreign policy towards Africa is something that may not appeal to France right now but it’s something that must be done. It’s undeniable that there will always be a strong relationship between France and its former colonies and, while there is nothing wrong with this reality, the new relationship must be built on mutual respect, and not be that of master and servant.

No comments:

Post a Comment