Forget Palestine, focus on ISIL

Danger Signals

The arrival of ISIL makes an Israeli-Palestinian settlement even more urgent. But Hamas is not ISIL, and ISIL is not Hamas.

By Gershom Gorenberg, American Prospect

Autumn 2014

In Hebrew, “black flag” refers to an immediate, glaring warning—as in, the “black flag of illegality” that figuratively flies over a military order that a soldier must refuse, or the actual flag put up by lifeguards to signal that the sea is too stormy for swimming.

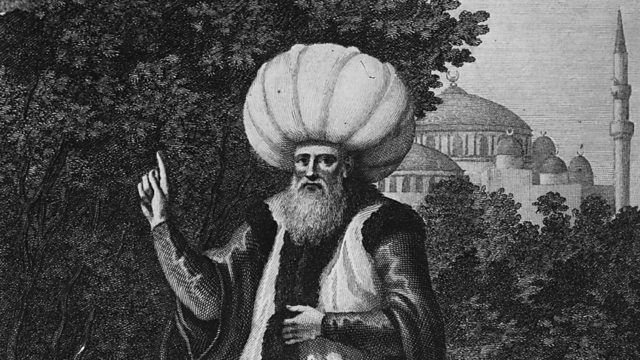

The symbolism of the color is entirely arbitrary. In Arab culture, a black flag recalls the battle standards of the Prophet Muhammad and of the Abbasid caliphate*, which ruled from Baghdad over a vast Islamic empire. Traditionally, the connotations are positive. In recent months, though, the two meanings have converged. Inscribed with the words “There is no god but God,” a black banner is now a symbol of danger, across the Middle East and beyond.

As the flag of the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant, also known as ISIL, the rebel organization in Iraq and Syria, the banner signals brutality, genocide, and the collapse of what was left of Iraq as a functioning state. It provokes horror, alarm, and sudden political shifts. Most obviously, the Obama administration has reluctantly returned to Middle Eastern wars, attempting to build a military coalition out of even more reluctant partners. Israel’s government points to the Islamic State as a catalyst of regional realignment that puts Israel on the same side as Sunni Arab states—and by implication allows it to put off, yet again, dealing with the Palestinian issue.

And therefore, I’d argue, the black banner is a warning of additional dangers—those created by America’s clumsiness in dealing with the Middle East and by Israel’s unwillingness to reach a two-state agreement with the Palestinians. To see why, we must look at the Islamic State’s rhetoric, its strategy, and its place in the wider regional conflicts—starting with its claim to have established a new caliphate.

If you took a moment off from being horrified by the Islamic State’s violence, you could find considerable irony in the group’s coronation of its leader, Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, as caliph, and his subsequent appearance at Mosul’s largest mosque in early July. Abu Bakr’s black garb, the choreography of the event, its venue—the Abbasid heartland—all were meant to appeal to Muslim memory of the Abbasid caliphate as a “civilizational golden age,” says Carool Kersten, a scholar of Islam at King’s College London.

Yet “people who look [to] the Abbasid caliphate usually point precisely at its cosmopolitanism, its pluralism,” says Kersten, co-editor of Demystifying the Caliphate: Historical Memory and Contemporary Contexts. “All sorts of Islamic groups were allowed to operate side by side, and Christians, Persians, and Jews all [had] their contribution to make.” The Abbasid age represents an Islam that embraces science, literature, and philosophy—an Islam that stands in stark contrast to that of the Islamic State. The rebels’ use of Abbasid symbols, Kersten suggests, might stem from “their own ignorance about Islamic history.” Or merely from intensely selective nostalgia: In the eighth and ninth centuries, the Abbasid caliphate was a superpower that ruled from North Africa to Central Asia and united most of the world’s Muslims in a single polity.

The Ottoman sultans were the last Muslim rulers to successfully claim the title of caliph. Since Kemal Ataturk abolished the institution, the theme of reestablishing the caliphate has recurred in Islamic political movements. It can signify a closely formulated alternative to post-colonial states, or a distant utopia, or be little more than a battle cry.

ISIL certainly rejects the existing state structure of the Middle East. Moreover, says Kersten, it appears to be heavily influenced by a jihadist strategic text that has been circulating since 2004, The Management of Savagery. That book describes the political division of the Middle East as an instrument of control by the “Jahili order,” meaning the reign of those ignorant of Islam.

None of this means that al-Baghdadi is about to be recognized as caliph by large numbers of Muslims, or even by other movements that call for a caliphate. It is “very difficult to take a claim to a universal leadership over Muslims seriously when those making the declaration appear to declare anyone who is outside of their group … as either sinful, deviants, or disbelievers,” political scientist Reza Pankhurst argued in a recent interview. Pankhurst is an adherent of Hizb ut-Tahrir, the Party of Liberation, an intellectually oriented pan-Islamic group.

The less bearable people find the present, and the less hope other political paths offer for more realistic improvement, the greater the attraction of such a vision and the extreme means used in its service.

But the Islamic State’s caliphate claim does help explain how the organization attracts recruits and a wider circle of support. ISIL purports to offer the immediate restoration of an imagined glorious past. The less bearable people find the present, and the less hope other political paths offer for more realistic improvement, the greater the attraction of such a vision and the extreme means used in its service.

Thus, one force creating support for ISIL is “disappointment with the Arab revolutions” of recent years, says Ofra Bengio, a senior research fellow at Tel Aviv University’s Moshe Dayan Centre for Middle Eastern and African Studies. That’s coupled, she says, with the attraction of a group that presents startling victories along with an ideology that promises “to get rid of all those who have failed.”

The list of failures begins long before the revolts of 2011. Pankhurst describes Hizb ut-Tahrir’s founding as a response to the Arab military defeat by Israel in 1948. Another defeat, in the 1967 war with Israel, widely discredited secular pan-Arabism and created an opening for movements that present Islam as a political program.

More recently, “Islamicists who were willing to take a procedural view of democracy and participated” in it “all felt cheated,” says Kersten. A key example is the short-lived rule of the Muslim Brotherhood in Egypt. It’s true, Kersten says, that the Brotherhood’s Mohammed Morsi “made massive mistakes” as president, and that there’s reason to suspect Islamicist parties of seeing democracy as “one man, one vote, one time.” Yet Morsi’s overthrow left advocates of working within the system feeling cheated, and increased potential support for a much more uncompromising approach.

Israeli border police officers carry the flagged wrapped coffin of Druze Israeli Chief Inspector Border Police officer Jaddan Assad, during his funeral procession in the Druse village of Beit Jann on Mt. Meron in the Galilee, northern Israel, Thursday, November 6, 2014. The officer was killed by a Hamas militant who slammed a minivan into a crowd waiting for a train in Jerusalem, killing one person and wounding at least a dozen before being shot dead by police.Photo by Ariel Schalit / AP

All of which brings us to the Palestinian-Israeli arena, and another chain of disappointments. Hamas, a wing of the Brotherhood, won the 2006 Palestinian parliamentary election largely because the Palestinian Authority (PA), under President Mahmoud Abbas and his nationalist Fatah movement, had failed twice over: It had not achieved Palestinian independence, and the autonomous PA regime in Gaza and the West Bank was riddled with corruption.

But Hamas’s election victory, combined with the organization’s terrorist record, brought an Israeli and Western boycott of the PA. In the end, Hamas was left governing Gaza alone, isolated and bankrupt under Israeli and Egyptian blockade. Another attempt to re-enter the political system by forming a unity government with Fatah this past June accomplished little—unless one counts helping to spark the war with Israel, after which Hamas celebrated its supposed victory in the rubble of Gaza.

Hamas would put all the blame on its Palestinian rivals and Israel. But this doesn’t remove the sting: Neither by waging war nor by waging politics has Hamas fulfilled the hopes of its supporters, or succeeded where Fatah failed. Meanwhile, the Islamic State scored lightning victories this summer and announced re-establishment of the caliphate.

During one ceasefire in the Gaza War this summer, the Bethlehem-based Palestinian Centre for Public Opinion conducted a poll in Gaza that included the question: “Do you support or oppose, in general, the …Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant?” The pollsters highlighted the fact that 85 percent of respondents answered “oppose.” Just as important, though, fully 13 percent said they supported the jihadi organization.

If one equates Hamas and ISIL, as Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu says he does, this hardly matters. But the two groups aren’t the same. Along with its rejection of Israel’s existence and its disregard for the lives of civilians, in Israel and in Gaza, Hamas has its pragmatic side. It has negotiated indirectly with Israel; it has enforced ceasefires and prevented rocket fire by more extreme Islamic groups; it joined a unity government under President Mahmoud Abbas, who is committed to a two-state outcome. The support of one-eighth of Gazans for ISIL is a sign that despair can lead people to positions much more radical than those of Hamas.

By refusing to distinguish between Hamas and the Islamic State, Israel does nothing to stop radicalization. The way to reverse the process begins with understanding that achievements by Palestinian moderates can be successes for Israel. The best way to make the promise of a new caliphate irrelevant is to work seriously with Abbas and Fatah to create a Palestinian state in the West Bank and Gaza. Which brings us back to America’s dwindling influence in the region.

“America will lead a broad coalition to roll back this terrorist threat,” President Barack Obama said in his September 10 speech on the Islamic State. Obama’s only allusion to the ethnic-sectarian conflict in Iraq was asserting, somewhat prematurely, that the country now had an “inclusive government.” Obama did lay out a strategy for a new stage in the war against terrorism. The Islamic State’s own plan of action didn’t receive a mention.

To better understand that, let’s go back to The Management of Savagery. (The name of the author, Abu Bakr Naji, is presumed to be a pseudonym.) The book denounces any perceived influence on Islamic political movements by Western ideas, secular or religious. But it shows the immense influence of one stream of Western thought—the ideologies and strategies of modern political terrorism, as developed in European revolutions and anti-colonial armed struggles. To this, it adds careful attention to manipulation of 21st-century media. The mix is then given a veneer of religion as principles of jihad.

Violence that seizes media attention, the book says, attracts new recruits who will be “dazzled by the operations …undertaken in opposition to America.”Savagery affirms the value of what previous revolutionaries called “armed propaganda,” with the United States as a particular target. Violence that seizes media attention, the book says, attracts new recruits who will be “dazzled by the operations …undertaken in opposition to America.” It also provokes the United States to act directly rather than through proxies in the Islamic world, eventually revealing American weakness. Extreme violence is also described as a means of “inflaming opposition” and polarizing the masses, who will find that there is no safe middle ground, no way to stay out of the fight.

Viewed in this light, the U.S. decision to intervene after the beheading of American journalists appears to be just what the Islamic State sought. This isn’t proof that American intervention is wrong. It does reinforce the impression, unlikely to improve America’s image in the region, that the murder of two Americans prompted air attacks and support for opposing groups of Syrian rebels, when neither the Islamic State’s atrocities against the Yezidi minority nor three years of civil war in Syria succeeded in doing so. It’s also a warning for the future: Washington needs, finally, to understand the strategic thinking of terrorists and consider how its own actions can outflank that strategy.

Volunteers in the newly formed “Peace Brigades” raise their weapons and chant slogans against the al-Qaida-inspired Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant during a June 21, 2014 parade in the Shi’ite stronghold of Sadr City, Baghdad, Iraq. Former rivals now often find themselves in an uneasy alliance as they seek to combat the Sunni extremist group. Photo by Khalid Mohammed / AP.

To avoid another pitfall, it’s essential to remember that the Islamic State is a Sunni group. While it is fighting other Sunnis, it’s also part of the multi-sided ethnic-sectarian war raging across Syria and Iraq. Before 2011 in Syria and 2003 in Iraq, these regimes “were like little Ottoman sultans” who held together a mix of religious groups and nationalities by force, much as the Tito regime once did in Yugoslavia, says prominent Syria expert Joshua Landis, director of the Center for Middle East Studies at the University of Oklahoma. Now, he says, religious identities such as “Alawite” and “Sunni” have “become much harder ethnic identities.” Ethnic cleansing has become a feature of the fierce conflict.

America’s conundrum in Syria has received considerable attention: To attack ISIL risks helping the Alawite Assad regime. Regionally, the Alawites are identified with Shiites, so America also risks being seen as fighting for Shiites against Sunnis.

“The Americans allowed the Shiites to do whatever they wanted,” and the result was ethnic cleansing.

In Iraq, though, the United States has already stumbled into this trap. At the end of August, American airstrikes against ISIL helped Kurdish peshmerga fighters and Shiite militias allied with the Iraqi government to break the siege of Amirli, a Turkomen Shiite town in northern Iraq. The Americans “didn’t pay attention” to the fact that Amerli is surrounded by Sunni Arab villages, says Professor Amatzia Baram, head of the Center for Iraq Studies at the University of Haifa. “The Americans allowed the Shiites to do whatever they wanted,” and the result was ethnic cleansing. “The militias are not just dangerous,” he says, “they are fanatical.” The Obama administration, he argues, must give help to the Iraqi government on the condition of using a more disciplined army to drive ISIL from Sunni areas.

The original American mistake, Baram says, was the assumption that U.S.-style one-person, one-vote democracy could be imposed on Iraq, ignoring the internal divisions. In 1990, he recalls, he met in Europe with a “very senior” member of the Iraqi Shiite Dawa Party, who compared Iraq to “a donkey and a rider”—the Shiite majority as the donkey, the Sunnis as the rider. “All he wanted to do was reverse the order,” Baram says, not to bring about democracy. Elections allowed the Shiites to do so, and accelerated the breakup of the state.

At this moment, Baram argues, the United States has the leverage to insist that the central Iraqi government work on the basis of parity: equal representation for the ethnic-religious communities, and “nothing moves forward without compromise” between them. Iraq can survive as a state only if it is federalized, with power transferred to autonomous regions, he says. Syria, Baram suggests, might best be divided into three countries—Kurdish in the northeast, Sunni in the center, and a secular Alawite regime in the West. But that optimistic scenario could well be wishful. The pessimistic prognosis is continued chaos.

Palestinians carry the body of Mohammed Jwabreh, 21, during his funeral in al-Aroub refugee camp, near the West Bank town of Hebron, Tuesday, November 11, 2014. Jwabreh was hit by a live bullet in the chest in clashes with Israeli security forces Tuesday. Photo by Mahmoud Illean / ASP

There are two lessons here for the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. The first is for the Israeli right: The attempt to maintain a single state where Jews have power and Palestinians do not is doomed, even if the date of the explosion is unknown. The second is for foreign proponents of a “one-state solution” based on one-person, one-vote, most of whom see themselves as being on the left: They are, ironically, proposing to repeat the mistake of the Bush administration in Iraq, imposing an American model that focuses on individual rights and ignores the reality of communal identities.

As of this writing, the Obama administration is putting together a Mideast coalition of the irresolute to fight the Islamic State. On the surface, every country in the region has reason to want ISIL defeated. In reality, each has contrary interests. Turkey’s top priority, as Baram notes, is the fall of the Assad regime, and it fears strengthening the Syrian Kurds. Saudi Arabia is concerned about ISIL, but more concerned about Iran—and the Islamic State is a threat to Iran’s Shiite allies in Iraq.

Nonetheless, Netanyahu has greeted the coalition against ISIL as one more sign of a Middle East realignment that puts Israel on the same side as Sunni Arab governments, adding to a shared fear of Iran. “They’re re-evaluating their relationship with Israel and they understand that Israel is not their enemy but their ally,” he asserted in a speech about terrorism on September 11. Implicit in Netanyahu’s message is that common interests with Israel have pushed the Palestinian issue off Arab leaders’ agenda.

Those who don’t want to solve this [Israeli-Palestinian] conflict are the ones who will lead us in the end to a bloody battle with beheadersJustice Minister Tzipi Livni, whose advocacy of a two-state agreement has virtually made her the leader of an opposition faction within the government, rejects that thesis. The condition for an alliance with Arab states is renewing peace talks with the Palestinian Authority, she asserted after a meeting with Netanyahu, the day before his speech, adding, “Those who don’t want to solve this [Israeli-Palestinian] conflict are the ones who will lead us in the end to a bloody battle with beheaders.”

Baram backs up her doubts. Before the war in Gaza, he says, he attended a meeting with a senior member of the Saudi royal family and a younger, rising Saudi figure. The former implied and the latter said explicitly that “Israel has to do something about Palestinians, or we cannot get married.”

Netanyahu, yet again, is engaged in either spin or wishful thinking. The realignment he wants depends on reaching the peace agreement with the Palestinians that he has evaded. The sudden rise of the Islamic State, with its videoed horrors and its promises of renewed Islamic glory, hasn’t changed that. Rather, it’s a warning of where Palestinian despair may lead, and of the potential consequences of maintaining what has become a de facto single state between the Jordan River and the Mediterranean.

The black flag is a warning, but it must be read correctly.

Notes and linksRiver to Sea

Gershom Gorenberg is an American-born Israeli historian, journalist and blogger, specializing in Middle Eastern politics and the interaction of religion and politics. He is currently a senior correspondent for The American Prospect. Gorenberg self-identifies as “a left-wing, sceptical Orthodox Zionist Jew. from Wikipedia

The Abbasid [pron. A – bars -id] Caliphate, the first Muslim ‘golden age’ is the subject of an episode of BBC Radio 4’s In our Time, The Abbassid Caliphs

Why ban Hizb ut-Tahrir? They’re not Isis – they’re Isis’s whipping boys, CiF, February 12th, 2015. Australia and several central Asian states have banned Hizb ut-Tahrir. British Prime Ministers from Blair to Cameron have toyed with the desire to ban them in the UK but have been advised against it.

No comments:

Post a Comment